“What Was It Like? Stories by LGBTQ Elders” is a new program by I’m From Driftwood, in partnership with Comcast, the nation’s largest cable provider, and SAGE, the country’s largest and oldest organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ older adults. Learn more about the program here.

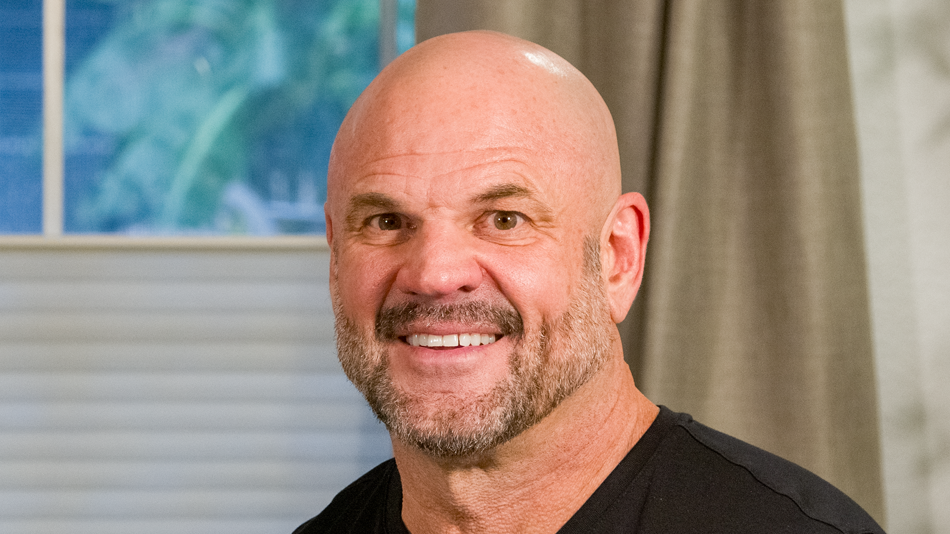

Richard Wandel’s stories were found with the help of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

Richard Wandel’s 7 Video Stories and transcripts can be seen below.

“1960s: In Retrospect, I Think Of Him As My First Love.”

I had this friend in in high school. He was clearly my best friend. We didn’t use words like that necessarily, but he was my best friend. His mother and my mother had been friends from childhood also, so it was very much two families who were friendships. And we had both moved to a new neighborhood, the same neighborhood, and so we began to see each other regularly and hang out and whatnot. And there was a wider crowd but he and I were were real friends and we used to hang out over at his place.

And we started to see each other separately sometimes, outside of the crowd, just over at his place. Both his parents were usually out during the day so we would be alone in the house in suburban Long Island. One day, we we were building this model city. You know, a plank of plywood and and cardboard houses and whatever. And so we were kind of at that stage where that kind of stuff was fun. I think with his suggestion, but I’m not sure which, we also started to play a bit with each other and did some jerking off.

We didn’t define it in any way. We didn’t even think in terms of homosexuality or anything like that. It was simply fooling around. Experimenting.

But there was a lot of guilt attached to it. I was raised a Catholic, went to Catholic school, both grammar school and high school, a Catholic school. So in those days, I’m talking about the the early sixties, in those days, masturbation with a mortal sin. You could go to Hell for that.

I would go regularly to confession. And I remember on one particular occasion confessing to this masturbation with my friend. The priest gave me absolution and all that stuff, but he told me that I had to stop seeing my friend. And even at that point, it didn’t make any sense to me. It did not make any sense that if you’re talking about love and all that stuff, that you should stop seeing a good friend. So I did not follow that advice.

Well, after a few years of being good friends with Mickey, suddenly my parents forbade me to see him anymore. Or to go over to his house. And I had no idea why. They did not say why. They just said, “You’re not allowed to do that anymore.”

We met secretly. Where we lived in the suburbs at that time, there were occasional plots of land, probably in dispute but for whatever reason didn’t have a house built on them. There would be a few trees that and, in this one case, I remember there was a half-dug hole. You kind of got down in it and felt like nobody could see you. And when we met, we would meet there and hang out.

I found out a good number of years later that the reason why we were forbidden is because his father had made, had attacked, sexually attacked, I don’t think successfully, but had sexually attacked my younger sister. And that was the reason for it.

I was a year ahead of him in school. I went away to school before he did. In that time period, he and his family moved elsewhere. I understand that at one point, he called my parents trying to find out how to get in touch with me and they refused to tell him.

I think about him a lot actually. I mean, in retrospect, I think of him as my first love. Although I certainly wasn’t anywhere near defining it that way at that time.

Kicked Out Of Monastery in 1969: “They Noticed My Homosexuality Before I Did.”

So I’d been, all together, I was in the monastery for six years. From the time I graduated high school onward. So this makes it about 1969. And it’s time for what’s called final vows. I was a member of the order already, under what’s called temporary vows, for three years, and then you take final vows. Only they have to pass on you first and say whether they will let you do that.

Well, in that last year, I was in Union City, New Jersey, leading up to this final vow time. Into the monastery came actually somebody who had been a Lutheran minister who converted to Catholicism. And he was considering of joining the order and becoming a Catholic priest. But because he was still not a member of the order, he had his own money and he had his own car. And we were right across the river from New York City. Union City, New Jersey, is right across the river.

So are we became friends. And we would go on many weekends, maybe that almost every weekend, one evening, we would drive into Greenwich Village and drink, of course, and have supper. Usually at a restaurant called Fedora’s, which I think still exists. Fedora is famous in the Village as the restaurateur who, and it being a gay restaurant. I, again, of course, at that time didn’t particularly have a concept of this, alright?

So this is going on it’s really annoying the hell out of my teacher, alright? Because I would, on the number of occasions, I would get to class late that first class in the morning. Or maybe even doze off in class. And then I, you know, got decent marks, alright? So that I think that probably annoyed them even more that this was true.

So it comes up to the end of that year and it’s time for them – they have a meeting, the faculty and the high honchos of the order have a meeting as to who they are and are not going to allow to take final vows. So I get called in at some point to the Director of Students office to be informed that, no, they’re not going to let me take final vows, which of course means you’re out of here, is what that usually would mean.

I was pretty stunned because I had no idea why. And they don’t tell you why. They just say this is the decision. You’ve been, essentially, you’ve been blackballed. You’re not, you’re not going to, we’re not gonna let you do this.

And I thought about it for awhile and I said, “Well, why don’t you let me take you year’s temporary vows again for another year.” You know, try to do it this way. And they agreed to that. So I went down for – as a summer project, myself and a few others were going down to this house in Philadelphia and we were going to get real jobs and see what the real world was like. So I did that.

And so after I was there a few weeks or a month, I said no, I’m quitting. A kind of a “You can’t fire me. I quit.”

A number of years ago or maybe ten years ago, my monastery classmates started having reunions every few years. Well, there are two people in that class who are still in the order. They’ve been up in the various offices, you know, of that, have various degrees of authority within the order, and have seen all the records.

So one my classmates, I said to him one day, I said, “I don’t know why. Was it alcohol? Was it the gayness? What was it that made them say no?” And he told me that he’d seen the records and essentially they’d noticed my homosexuality before I did. He also told me that when they were saying no to me and about to totally throw me out, he and a few others stood up for me and threatened also not to take final vows if they didn’t allow me to do so. Of course, the compromise was to go for temporary vows, and then I quit.

My monastic life gave me some very good things. And, on the other hand, it was really, to use modern terminology, a really, really dysfunctional family at the same time.

So it’s a sifting out what good I took from it. Certainly my sense of ritual, I did. My sense of spirituality is partially from there. It’s no longer anti-sexual, but it is partly there. So that whole period remains an important period – training period, if you will, an important period in my life of finding out who I was.

First Meaningful Sexual Experience As An Adult: “I Knew That Meant I Was Gay.”

So in 1969, after having been in a monastery for six years, I left. And I returned first briefly to my parents house on Long Island. But very, very quickly found a job and moved into New York City. The first place I found to live was a small apartment just off of Times Square with a roommate who I met for the first time in looking for the apartment. It was a one room apartment.

And one night, I’m sleeping. There was very little in that apartment besides two beds on either end of the room. I’m on one side. He’s on the other. I wake up or half-wake and he’s sitting on my bed, and just kind of rubbing my leg. Scared the hell out of me. On the immediate level, I didn’t jump up and say, “What are you doing?!?” I just pretended to be slowly waking up, alright, so that he went back to is his own bed and there was never any confrontation between the two of us And then I quickly moved out. It really threw me for a loop. It frightened me.

My next apartment was on on 55th Street and about Ninth Avenue. I didn’t know this at the time until somebody started showing up at the door, but this gay man who was subleasing to me actually had this thing where truckers would come into town and ring his bell for a blowjob. That was his, that was his sexuality.

So now I’m here I am and I’m getting doorbells rung. I’m just, “Yeah, I’m sorry, Peter’s not here. He’ll be back in three months.” And that’s fine.

But, in the meantime I went back to the last monastery I had been in across the river in Union City, New Jersey.

And there was this one particular young man and I was gonna stay overnight in the monastery. That’d been pre-arranged. I don’t remember exactly how it happened. It probably happened with a touch here or there. But we wound up together in the monastery – he was not a member of the monastery, he was in the neighborhood – in the monastery and having sex as I knew it that time which was basically frottage.

And the interesting thing to me was I noticed that it wasn’t just about getting my rocks off. I was, in addition to enjoying that aspect, was also interested in kissing, in seeing, in hugging. It had a deeper meaning than simply a genital meaning to me. And I noticed it for the first time with this young man. In the monastery, of all places.

So my initial reaction was somewhat of panic. But I pretty well, I guess, had confidence in myself, knew that I was basically a good person, and was able to pass through that very quickly. It’s not just about the good feel of an orgasm, of physical orgasm. It’s more much more than that. I knew that meant that I was gay.

Following Gay Man’s First Protest In 1970: “I Knew Where My Place Was.”

It was in the summer of probably 1970. I had recently, the fall before, left the monastery that I had been studying in and living in for the past six years. I was living in Brooklyn and I had just, in that spring, come out to myself. Just for the first time. I’m at the age of 24. I, just for the first time, said to myself, gosh, I’m gay. Or I probably used, in my head, the word “homosexual.” Whatever.

I found out probably a report of a demonstration of something. I went to a meeting, probably one meeting at this point, of the Gay Activists Alliance, who were meeting in Manhattan at Holy Apostles Church on Ninth Avenue at that time. And because of that, I knew that there was going to be a demonstration, but I wasn’t planning on going. I wasn’t, I wasn’t quite ready to take that step.

I lived in Brooklyn but I’d been over in Union City, New Jersey, for the weekend with friends. The way home then would be to take a bus to Port Authority, walk over to Sixth Avenue in the D line. That is to say, walk through Times Square over the Sixth Avenue, where I would get the train to go home to Brooklyn.

So as I’m walking through Times Square, there’s this demonstration. It was a combination demonstration of the Gay Activists Alliance and the Gay Liberation Front. G.A.A and G.L.F. The reason for the demonstration, and this was so typical in New York that, especially if it’s going to be an election year, politicians quote unquote cleanup Times Square. And among other things, that meant for the police to go and arrest, or at least hassle and often arrest anybody who even in their minds looked gay. So the demonstration was in response to this.

And I say, what the hell. They’re here. I’m here. Let’s do this. And this was a really pretty simple demonstration in the sense that it was simply a picket line with banners and signs. But no civil disobedience intended, no disruptive – nothing. Just a very simple one.

And then somebody got the bright idea to go down a few blocks away to the precinct that was chiefly the ones who were doing this harassment in Times Square. So we did that. But people were exuberant, so somebody says, “Well, let’s” – I don’t even know who that somebody was, I don’t think anybody would know who that somebody was, right – “Let’s go all the way down to the Village. “

Now, when we arrive at 8th Street, we arrived at 8th street and Sixth Avenue. And a couple of things were there. One is that there was, still existing then, doesn’t exist anymore, the Women’s House of Detention, the temporary prison for for women was on that corner. The other thing was that 8th street between Sixth Avenue and probably Fifth, was closed to all traffic as being a summertime mall, pedestrian mall, until midnight.

We kept circling the women’s house of detention. And then we moved onto 8th Street, which was for pedestrians. And we were having a good time – we were primarily, at that point dancing, having fun. So midnight comes along. And at midnight, it was supposed to return to cars on that street. It was no longer supposed to be pedestrian. The police wanted to open it up for that purpose. And we didn’t want to go. And we did not go. So you had this standoff.

I noticed a couple of things. I noticed that there were some provocateurs who might throw things at the police but from a safe distance by throwing them over the crowd. On the other hand, I also noticed that the police, when that happened, would just pick somebody small nearby to beat the crap out of. At least metaphorically, I saw blood on the streets that night.

By the time I got to Brooklyn that night, got back home to Brooklyn, I think I was a changed person. Before that, I was a young man figuring out what to do with myself. After that, or from that night on, I was a member of a community. A community that was important to me.

And I knew who my community was and I knew where my place was, and, in general what I would have to do. Not specifically what I would have to do, but in general, what had to be done. And I would do it.

Protest At Radio City Music Hall: “There’s A Great Deal Of Fun In Standing Up For Yourself.”

It must’ve been about 19, probably 71, maybe 70. I’m bad at dates but in that kind of time period. I was a part of the Gay Activists Alliance in New York. The Mayor of New York at that time, John Lindsay, was very much a liberal. But liberals even at that time were people who would quietly try to help, but would never be public. And we knew that it was important for for gay rights that it be public. That that little quiet “shhh” on the side was insufficient.

So we had, the Gay Activists Alliance had a many month campaign to do that to John Lindsay. And on one of these occasions, it was gay pride week of that year. We decided to harass him, I think is probably the right word, for that entire week.

John Lindsay, at that time, was – it was early primary season. John Lindsay was going to run for president. So he had this big fundraiser at Radio City Music Hall. We were going to do two things. We were going to certainly have pickets outside. Loud pickets – shouting, screaming. But we also had managed to get a half dozen or five or six tickets to the event itself. We were going to do a disruption inside Radio City Music Hall as well as this demonstration outside.

The way this is going to work, it was the world premiere of the film, “Hot Rocks.” So it was in conjunction with that, at Radio City Music Hall. So, of course, before the film, though, they were gonna do speeches.

So first out on the stage was a very popular liberal comic, comedian, at the time by the name of Alan king. So he came up, he came up to the mic, did a few jokes and then introduced the mayor John Lindsay. Steps to the side. John Lindsay comes out, steps up to the microphone. And as he begins to speak, not all of us inside, but one person, the first one being, I believe, Cora Porada, stands up and starts yelling, “John Lindsay, what are you going to do about the oppression of gays in New York City?”

Of course, there are cops and security people who are going for her immediately to get her out of there. We all had, very popular at the time for some really ridiculous reason, was these handheld sirens, which somehow we’re supposed to protect you from a mugging or something, right? You could pull the pin on the siren and it would go off. We, each of us, had one of those. So as they’re almost about ready to grab Cora, she pulls the pin, throws the pin in one direction and the siren in another. And, of course, gets led out of Radio City Music Hall.

John Lindsay comes back and starts again. The second person stood up and did the same routine. There were four or five of us who were able to do that. It forced the John Lindsay off the stage, to be replaced by, actually, a cartoon which was preceding the film that they were showing.

So a bunch of our people also wound up being in the balcony. And as we were doing this down below, giving John Lindsay a hard time, they just took a bunch of flyers and went over the seats and raining down from the balcony.

I think I remember Radio City Music Hall in particular among a host of other actions that we did because it just kind of had everything in there. It certainly had a just cause. It had a sense of power in it. It had theatrics in it. It had a certain cleverness in how we did it.

When I tell stories about zaps as we call them, various actions, I think what I’m trying to say, aside from the fact that it’s a lovely memory that I like to remember, what I’m trying to say is that we had a great deal, there’s a great deal of fun in standing up for yourself. For any of the issues today, whether it’s LGBT rights or others, do it. It sets up your life in a way that you will enjoy and be proud of, so get out there and and do it.

One Week As A Gay Activist in 1971: Rejection, Assault, and Gunshots.

If you want to have an idea of what it was like even in New York City or New York State in the early seventies, there’s probably no better way than to tell you about a week’s events – one week’s event – when we when we walked Albany and the aftermath.

So it’s about probably 1971. I’m now president of the Gay Activists Alliance. There’s been an effort statewide for different groups, gay groups, within the state to form coalitions to work together on the state level, which at that time would be about sodomy repeal. It was illegal for two men or two women to sexually be together.

So the tactic more than anything else has always been and remains today: come out of the closet. As President of the Gay Activists Alliance with others in the organization, we decided that GAA would do a walk from Times Square to the state capitol in Albany. It’s about, if I remember correctly, I think it’s something like 155-point-something miles. And it would take us roughly a week to do so. There’s about a ten or twelve of us who are doing this.

The first night – we had also support staff with cars who were doing things like figure out where the hell we were going to sleep at night, because that was not all settled before we started. We just did that as we went along.

Our first night, we had accommodations in Scarsdale at a Quaker meeting house. The Quaker community, very, very early on, was a supporter of gay rights. This was an example of it. But their meeting house was a considerable distance away from Broadway.

So we find ourselves outside of a Catholic women’s college. It’s raining. Pouring rain. We can’t all get into one car. We gotta ferry back and forth to we were staying for the night. We noticed that this activity going on. It’s in the evening but there’s activity going on in the college. Apparently, they were having some sort of event. So we asked for permission to step into the lobby to stay out of the rain. They said no. They would not allow us to do that. But we saw, there was like a separate building which was restrooms. We all immediately piled into the men’s restroom and they wouldn’t come after us there.

It took us about a week to reach Albany. We stand at places like Kate Millet’s, who is a feminist writer and open bisexual, at her house outside of Poughkeepsie. We stayed actually at a Catholic monastery also on one night and at Bard College on another.

But while we’re on our way there, one day, there were some people had kind of fallen behind a bit for whatever reason. And they were shot at near Rhinebeck, New York. So they came up and told us about this. They’re pretty upset, obviously. I mean, clearly, the person did not intend to hit them, otherwise he would have, alright? But nevertheless, so we decide certainly we should go make a complaint to the police. The police in that neck of the woods are the state police and they have a barracks in Rhinebeck, New York. And so that’s where they went. On presenting the complaint, they were more or less verbally thrown out of the place with the statement that “You’re lucky it wasn’t us – we wouldn’t have missed.”

On another occasion, we asked for permission to stay in a barn overnight, which was run by or owned by a group of what, in those days, was called “Jesus freaks.” These are young, in a sense, hippyish, except they’re decidedly and openly Christian and into Jesus. They told us they would pray about it and get back to us and meanwhile we found someplace else to stay. Last we knew, they were still praying about it. I’m obviously being a little flippant here but what the hell.

Finally we get to Albany about a day early. At the same time, we were – the statewide coalition called New York State Coalition of Gay Organizations, NYSGO, was organizing a rally for the steps of the state capitol in Albany. So the idea was that’s where we would meet everyone. That was our culmination. We got there a day early so we stayed somewhere across the river because it’s important to make the proper entrance, alright? So we made our entrance after the rally was going on, with the crowds parting and us coming up through the middle and me as President of the Gay Activists Alliance up to the microphone. I have no idea what I said on that day. It was just too much of a rush.

We stayed overnight at various local gay activists’ apartments and went back the next day. We arrive back in New York City to learn that there had been a demonstration that evening at what was called the Inner Circle Dinner. The Inner Circle Dinner is an annual dinner held at the Hilton Hotel for politicians and journalists. And they do silly things and what not.

The people in charge of New York while I, the president, was away, had called up a demonstration because of various homophobic remarks that had been made by various politicians who were going to be at that dinner. In the process, they got beaten up. Specifically by the head of – at that time, the head of the firemen’s union, by the name of Michael Maye, who punched out a couple of people and who threw one person, Morty Manford of the Gay Activists Alliance, down the escalator.

So I got back to New York pretty tired, but the first thing I did getting back to New York was going to a couple of different emergency rooms to see my other people. Ultimately, I mean, no one was seriously hurt. We’re talking about black eyes and whatever the medical term is – contusions or lacerations or whatever the term would be. But nobody overnight in the hospital.

But again, that was the time. In one week’s time, we’re talking about being shot at. We’re talking about being rejected by various people when you just want to get out of the rain. Then coming back to being beaten up and going to emergency rooms. That’s what it was. I mean, that didn’t happen that way every week, but that was not a surprise that such a thing should happen.

Following The Funeral Of A Gay Friend: “I Left That Church Promising Myself Never To Go Back In.”

So after being a gay activist in New York City for about five years – so roundabout, sometime in the early seventies, it was time to move on. Originally when I left New York, went to a college town in Olean, New York, where I had given a talk a few years before, as a key leader, and therefore had contacts. That didn’t work out particularly well in terms of being able to get jobs and stuff.

So I met somebody in the nearest gay bar, which is a half hour away in Olean, New York, and then moved to where he lived, which was a small city in Pennsylvania. Bradford, Pennsylvania. Then I got involved with the local amateur theatre group.

Among the people in that amateur theater group with an older man by the name of Vince or Vinnie. And he was one of these people who everybody knew was gay but he would never say it, alright? And that was pretty much the way – except for me – the way things were done in that town. I was totally out. I was not going to go back into any kind of closet, so I was certainly totally out even while I was there. But my other gay friends including a lover at the time were in that category of believing nobody knows when everybody does.

Alright, so Vinny, Vince felt terrible about himself apparently. I mean, I didn’t realize this until afterwards but he felt really guilt ridden and terrible and committed suicide. So I went to the funeral. The city had one Catholic Church, we went there.

And there was this – I’m sitting there. I, at this point, still considered myself a Catholic. I’d not been going to mass regularly or anything like that, but I still certainly considered myself a Catholic. This funeral was just so weird to me because the priest, a young priest got up to give up the homily and he talked about how wonderful Vince was. And I knew that this priest didn’t know Vince at all. Had no idea. It wasn’t even that he knew him and had the wrong idea. He just didn’t – he was just faking it all the way. And more importantly, that this was the very – he was the emblem, if you will, this priest with the symbol of who taught him to hate himself.

For a long time, I had disagreed with a number of things of that the Catholic Church taught, notably homosexuality, of course, but also birth control, rights of women, all of that sort of stuff. But this was the “I’ve had enough.” So that was the turning point for me. I left that church promising myself never to go back in, except maybe for a wedding or funeral.

I reverted back ultimately to my love of mythology. And I discovered Wicca which is a very – it’s not authoritarian, it’s not particularly institutionalized, we don’t really talk a lot about items of theology, what matters is how you live your life. But I am a person who likes rituals so I need, if I’m gonna have a religion, I need one with rituals. So that was again and put an important turning point, in my relationship to my own spiritual life, not simply – obviously, in relationship to the institution of Catholic Church, but also in relation to my own sense of spirituality.

If a person is stuck in a religion that tells them that they’re evil, you know, whether by reason of homosexuality or anything else, then you have to look inside yourself and know yourself and know that you’re not evil. Therefore know that they’re wrong. Know that you’re a good person. It’s about – religion, if it’s for you at all, should be something to help you always further discover yourself.

Share