“What Was It Like? Stories by LGBTQ Elders” is a new program by I’m From Driftwood, in partnership with Comcast, the nation’s largest cable provider, and SAGE, the country’s largest and oldest organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ older adults. Learn more about the program here.

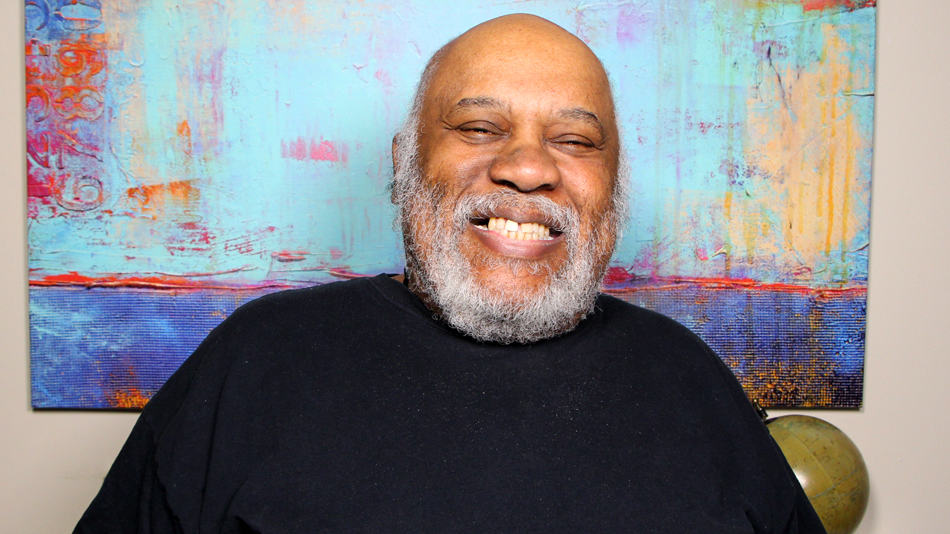

Donald Bell’s 7 Video Stories and transcripts can be seen below.

Dictionary Makes Gay Teen Feel Less Alone

One of the significant characterizations of the period that I spent in high school in the mid-60s – from ‘63 to ‘67 was that one day in one of our classes, the word “homosexual” came up. Most of us didn’t know what it meant but we were kind of curious about it. I suppose the teacher gave some cursory definition or whatever.

I carried the word with me and I wanted to find out more about this thing. There was nothing that I could find at either of my high school libraries. But we happen to have an old Andrew Carnegie library in town, and like all libraries in that period, it had two resources that were very important. One was the unabridged dictionary that’s always open on top of the stacks. And the other was the Encyclopedia Britannica.

So I went to the unabridged dictionary, and I looked this word up. And it occurs to me as I’m telling you this story that somehow when we actually heard the word, we also got the message that this wasn’t something we could just generally ask about. So I didn’t ask an adult about it or whatever. I knew that this was something I had to keep to myself as I was looking for it.

So I found the word “homosexual,” read the definition and all. But what really stuck out with me was that this page of the dictionary was smudged. So I wasn’t the first nor the only person who ever looked this word up. And that left some impact. I was like, “Wow. There are other people who wondered about this?” And I went to the Britannica. Same thing. The entry was smudged.

So, there are people out there somewhere that I didn’t know, that I didn’t see, that I wasn’t conversing with, who were looking up this word. And that sort of sums up the experience of being a gay adolescent at that time. You’re searching for something that’s not part of the general conversation, where there are no places that you can go to deal with it. You get the sense that it’s bad and that you need to keep it secret. But you gotta search for it. And then find that you’re not the only one, in fact. Somebody else is searching for it, too.

It made me feel, well, it made me feel sad because even recognizing that there were other people out there, there was no connection to them. There was no way that I could find out if there were another 15 or 16 year-old boy who was looking up this word and talk to him about it. And it reinforced the idea that it must be something wrong or else people would talk about it openly. So, that’s how that made me feel. So, I got the negative values associated with homosexuality in looking for meaning.

1960s: “I Was in a Process of Falling in Love at First Sight.”

One of my life experiences that I like to share dates back to my early teen years. Back in the 1960s, I was 19 years old and returning to university for my second year. At the time, I was recovering from a very unsettling first year. I was dating my high school sweetheart still, and we had thought since she also had a very disturbing first year that perhaps the solution to our problem was to get married and then one of us would switch to the other’s campus and we’d go through school and through life together dealing with these issues at the same time with each other. We mulled that over throughout that summer after freshman year.

And it got pretty late summer, so we decided instead that we return to our respective schools and we’d give it one more try. If things didn’t work out, we would definitely get married the summer after sophomore year. So I went back to school. I was a little early because I was an orientation leader. I’d moved into my residence hall and was settling in when I went down to meet my new resident adviser. Well, I knocked on the door and, you know, this man open the door. And I looked at him and then all of a sudden, I had what I can best describe as a Disney moment, because all of a sudden I had, you know, staffs of music floating through the air and there were birds chirping and butterflies. And I was in a process of falling in love at first sight.

This depth of passion, and just the spontaneousness of it, was overwhelming. And so I realized in that moment that this was a confirmation of my true sexual orientation.

So, after spending some time with him, I went back to my room and immediately convened a session with God. I was very upset because, as you can imagine, in the Sixties, coming to the realization that one is gay wasn’t exactly the most cheerful news that one could discover about oneself.

I thought and I prayed and I ranted and raved and meditated – did everything in the course of several hours in my room by myself. And then my final resolution was this: I knew that, as an African American man, that I had to make adjustments in my own head so that I could be proud of who I was. I had to reject the majority social narrative that black men were lesser people. And it occurred to me in sort of intersection that I had to do the same thing about being gay. The narrative about gay men was either that they were less then, masculine, or they were feminine, or they were perverts or some other kind of social pariah.

And so I was feeling that I was on the receiving end of two challenges. But I felt then, as I feel now, that to get through my life, I had to make changes in my own head and reject that narrative and find a positive way to be proud of being black and of being gay. And it meant, of course that I had to renegotiate my relationship with my girlfriend, my fiance. I did that as a function of being honest with her. I loved her enough to tell her the truth.

I had made what I figured was a moral decision of accepting myself just as God had made me. And I resolved to make that a positive experience, as opposed to the negative experience that general society said it was. You know, I am a black gay man, and I’m proud of every part of it.

Being Black and Gay in the 1960s: A Matter of Life and Death

My late teen years, when I was at university, were times that were really life and death-related times for people my age and people from my background. At that time, being black could get me killed. Not just lynched but I could disappear between campus and home, coming home, just out in the countryside. Being gay could get me killed. Of course we all knew what gay bashing was and there was certain [unintelligible] to doing that. And one of the responses to finding out that someone was gay was to spotlight that person and penalize them. And the penalty could go up to and include death, in violent reaction to finding out that someone was gay.

One of the significant experiences of my life as a young gay man happened my second year in college. I became involved in a sexual encounter with a good friend who lived across the hall from me. And we were pursuing that and at one point, he changed his mind and said we shouldn’t be doing this. And so we stopped.

He left and went to his room, a short while later coming back with his roommate who was a good friend to both of us. And the three of us sat down to talk about what had happened. In a spirit of support, the roommate suggested that probably the best thing to do was to go over to the Psych and Counseling Center and talk to someone about this. Now that was a good reaction for the times because the consequences of being gay at that time were very, very serious. They were life changing. If a man were rumored to be gay, it would be referred to the Dean of Men’s Office. And the campus culture was that if you got called from Dean of Men’s Office, you may as well pack your stuff before you go because you’re on your way out of university.

I followed the advice and went to the counseling center and there the therapist told me that this was just a phase. This happens to lots of young men and not to be that concerned about it and whatever, so he didn’t suggest that it was a major issue. He didn’t threaten to report me to the Dean of Men or anything like that. So I felt that I’d dodged a bullet.

I could’ve lost my student deferment, which would have made me eligible to go to war. Tremendous numbers of people my age, of course, were dying in Vietnam at that time. And for black people, that was especially true, because our black service members disproportionately served in Vietnam. So death was a reality all the way around.

“It Was Extraordinary”: Man Asks Man On A Date In 1967

Another significant incident from my youth, from my late adolescence, happened in 1967, my first year at university. I went away to school with a small group of students who’d gone to high school with me. So we had sort of a subgroup that formed on campus, where we kept our old high school network together.

And this involves very close friend of mine who went to high school into university with me. He found himself attracted to some guy, and he asked him out on a date! Now that might not sound extraordinary for 2017, but from 1967, it was extraordinary. So the story of this spread through our high school network.

And I was like,”He did what?” And not only did he do it, but he was strong enough to be matter fact about it.

When the young man reacted out of out of fear, out of panic, out of outrage, you know my friend simply said to him, “Look. It’s a date. All you have to say is yes or no.” He was rational, he was controlled, he was outspoken. He had voice at a time when many of us did not have voice.

And it just makes so much sense it. It leant reason to the whole idea of social acceptance. So if it could be presented so rationally for another person, why couldn’t we presented rationally to ourselves. You happen to be sexually attracted to people of your same gender. What’s so difficult about that? So it helped, again, normalize my own experience. So I carry that with me always.

“[My Mother’s] Number One Duty Was To Be An Accepting Parent.”

I went to my first march on Washington 48 years ago in 1969 in the moratorium march against the war. And what made that significant was that about fifteen thousand people from my campus went and we crossed the country in motorcoaches and in school buses and slept on church basements and the whole thing. All of those rugged things that one is supposed to do when protesting.

An important aspect of the fact that we all went to Washington to march against the war was that we sorta went in secret. Nobody fessed up to their parents before they left because you don’t want mom and dad saying, “No, you can’t do this.” So, after all, we were young adults. We were out on our own.

So we went. When we came back, of course, the guilt was starting to get to us so we better fess up to mom and dad that we’ve been to the to the March in Washington. And so a group of us that had traveled together, who lived together in my residence hall floor, we got together in one room and we decided to make the calls all together as a group from one telephone.

And some parents were pretty cool with it. Some parents, you know, admonished us not to do anything that foolish again. But one parent’s results or response was really significant to me and I’ll never forget it. And it was one of my best friends, talking on the phone and his face went kind of ashen.

When he hung up the phone, we said “What happened?”

And he said, “My dad just told me that I’m no longer his son.”

When I called, when I made my call – I made my call the last of the calls that were being made.

And my dad picked up the phone and I ask if mom were home and he said “Yes” and I ask if she get on the extension and she did.

My dad says, “Yeah, what is it?”

And I said, “Well, I’m just getting back from Washington because I was at the March.”

My dad says to my mom across the extension, “See there? I told you that was that boy that we saw on television.”

And they started to laugh because they anticipated that this was something that I would do. So no admonishment, no rebukes, no lectures. They just accepted it.

And later in life, I was my mother’s sole caregiver for 18 years. Into the process of having all of the conversations, she did not want to go with anything unclear and I did not want to let her go with anything unclear.

I said to her one day, “Mom? Now I think I know the answer to this but I just want to ask you because I want us to talk about it. If I’m wrong in what I’m what I’m thinking. Now I know that you are a woman of faith. You’ve always been, you’ve always exemplified that. But let me ask you this – does my sexual orientation compromise your sense of faith?”

She looked at me as if I had lost my mind.

And she said, in pointing her finger, “You are my son.”

And she was done with it. And of course what she meant was that, as she had always exemplified, that the stewardship of parenthood was more important to her than any religious dogma whatsoever. And that she felt that that was her number one duty in terms of her children, was to always be an accepting parent. And she always was.

Well, the connection between my experience coming back from protesting the war and my experience of doing an assessment of what my relationship had been with my mother and my parents throughout my life was simply this: I benefited from the support that they offered me. Neither politics, like the war, nor religion like the faith issues, came between us. We had a relationship and that relationship – that parent/child and later parent/adult child relationship was never compromised by things that affect the lives of a lot of other people and really make a difference in the emotional lives of LGBT people.

Racism At A Gay Bar: “It Was Shocking. It Was Hurtful. I Teared Up Right There.”

I did have some experiences from later in life that were significant to me. One happened about 20 years ago in the late nineties. I was in my mid-forties. I was at home. And at the time I was living in the south Chicago suburbs. And I had a bar in one of the towns that was a gay bar that served a huge swath of the south suburbs. But it was our community home. It was very diverse. It crossed racial lines, class, gender lines, both men and women were part of this. And these were people that I knew.

I happened to be the only black person in the circle of about six guys. The story was about something. I don’t exactly remember what the story was about. But I remember that all of a sudden, there was a racial reference in response to one of the guys who were standing in the circle. And he said to me that he and his partner were not attracted to “the dinge”.

At first, I didn’t believe what I was hearing and I had to really think through exactly what he meant. And it occurred to me that “the dinge” is that is actually a UK slang term for people of color. I was just surprised that I was not just another person, another member of the community, of our family circle to him, and that, in fact, even after this long association, race still made a difference.

So it was shocking. It was hurtful. I teared up right there. I didn’t break down and boo-hoo but it just struck me as so very sad. One of the guys came to my defense and told him that he was unbelievably offensive and had offended everybody, and that what he said was not appropriate. And I appreciated that support because I was unable to respond because I truly was stymied by this situation. It was the loss of a friend. But as I recall later on, his partner was not there in the circle, did come apologize to me later. So that was gratifying.

When someone who is not an African American man says to me, “I’m not into black guys” or “I’m not into the ‘dinge’”, that person is saying, “I don’t see you as an individual. I see you through the prisms of my racial training, my racial prejudices.” And you cease to be an individual but you’re a part of that. So there’s no basis for personal relationship anyway.

Living In LGBT-Friendly Senior Housing: “We Live Like Neighbors. And That’s A Good Thing.”

Today, I am 67. Well, actually, 67 and a half, as my grandson would tell you. And that’s significant. I’ve made it through a long way. I am in the middle of transition because my life has changed. My parents are now both gone. My children are grown. And I’m the grandfather of seven. So they’re involved in their lives, and I am now involved in my life. And I moved from my home in the south suburbs to the center of town, to Boystown, to “Homo Central” as we call it out in the boondocks, to move into Town Hall. Town Hall is the fourth development in the United States that developed specifically to be LGBT senior friendly.

What happened to Town Hall when we opened up – and understand that this residence is owned cooperatively by the Chicago Housing Authority, Heartland Alliance, and the Center on Halsted, our LGBT community center. So there was a huge lottery for spaces. It’s a building that has 79 units and we currently have 93 residents. There were hundreds of people in the lottery for spaces in this building and they came from all three of those sources.

Well, when they finally filled the building, they ended up with a breakdown by sexual orientation that was 60/40. Sixty percent LGBT, forty percent straight. I have some questions about that particular breakdown. I think it could have been less, but there are other issues I think could have been done with it.

It appears that there were many people who came from outside of the LGBT community who were not advised that they were moving into a residence that was intending to be LGBT senior-friendly. And I happen to be sitting in one of the public spaces one night after we’d just moved in. And there are about a half dozen other people around. These people were from the south side and the west side and they did not know that this was Boystown, that this was Homo Central in Chicago. They’d never heard of it. And so the first they heard that they were in the LGBT-friendly senior building was when we all were together for our first residents meeting.

And so they said in a small group discussion, “Well, what’re you going to do about it?” My fear sitting there, listening, was it could have ended with people say really homophobic things, and saying, “I don’t believe in this. And we’re gonna blow this up and make a big stink out of it.

But they did not have a homophobic or a heterosexist reaction to the situation in the way that they could have. They had a good, individual, personal reaction to it, which was, “Let’s stop and think about this. You know, what is the reality of our situation?”

And they said, to their credit, “Oh we’re not going to do anything about it. Look at what we got. We’re in a fabulous neighborhood. We’ve got grocery stores. We’re grocery store rich! The place is new. It has no vermin. We’re staying!”

And it occurred to them that the presence of gay people was not threatening to them as straight people. Certainly not as threatening as leaving this residence and having to fend for themselves someplace else. So that was good that they reacted rationally rather than emotionally.

Interaction amongst my neighbors happens in the community room, which we have renamed the “Rainbow Room.” And it happens on the terrace and it happens in front of the mailboxes and things like that. And people know each other, they know each other by name, they’ve worked on projects together, they garden together, and that has served us well and that’s because of the effort that the actual residents put into building community, and not because of the foresight in planning of the developers of the community.

For those six people who were in the common area with me that night, who were engaged in this conversation that had me sort of speechless because I was afraid of where it was going to go, these people that I see and I interact with everyday. We are not our social classifications to each other. We are individual people. We know each other by name. We feed each other. We share with each other. We check on each other. We make sure that people are healthy. We live like neighbors. And that’s a good thing.

Share